Local pundits thought that the election of McKinley in November, 1896, foretold a good season for Ben Lomond’s dueling hotels. The Mountain Echo of Boulder Creek agreed, adding that, “Ben Lomond is fortunate in her two leading citizens and property holders,” praising the “enterprising spirit” of the rival developers “as they vie with each other in improvements.”

On the south side of town, the Hotel Rowardennan continued to grow. The Sentinel predicted that it would, “be crowded with beauty and fashion from San Francisco and across the bay.” Thomas L. Bell lost no time replacing his burnt-out residence with two good-sized buildings full of guest suites. In its initial season, guests of his Hotel Rowardennan had enjoyed the benefits of “LakeBell.” The high dam that formed the lake also furnished water power to provide light for the resort’s buildings and grounds.

Meanwhile, on the town’s northern boundary, D. W. Johnston, owner of the Hotel Ben Lomond, planned his own dam, “for boating purposes.” Four skiffs would ply the enhanced river waters. Johnston also ordered a dynamo from the East and prepared to install 170 incandescent lights. Wires were distributed around the lawn and along the river to create “a veritable fairyland at night.”

The completion of the Hotel Ben Lomond dam provided unexpected amusement for early-season guests at the Rowardennan. A popular feature at LakeBell was a large raft, with room for forty loungers. Intent on fun, a small crowd piled on, disregarding the fact that the lake had not been allowed to fill. When the unofficial captain attempted to land the awkward craft, he slipped down the steep muddy bank into the water. “The kids thought it great fun,” commented the Sentinel.

For the next few years, Ben Lomond’s hotels vied on almost equal terms. Attempts to go one-up were quickly matched. Both built tennis courts, bowling alleys, dance halls, club houses, etc. Ben Lomond advertised an elegant croquet court, while the Rowardennan offered nine holes of golf. There was, however, one particular distinction. From the first, the Rowardennan pursued a policy of exclusivity. As one version of its letterhead proclaimed, the management refused to “cater to members of the Hebrew persuasion.”

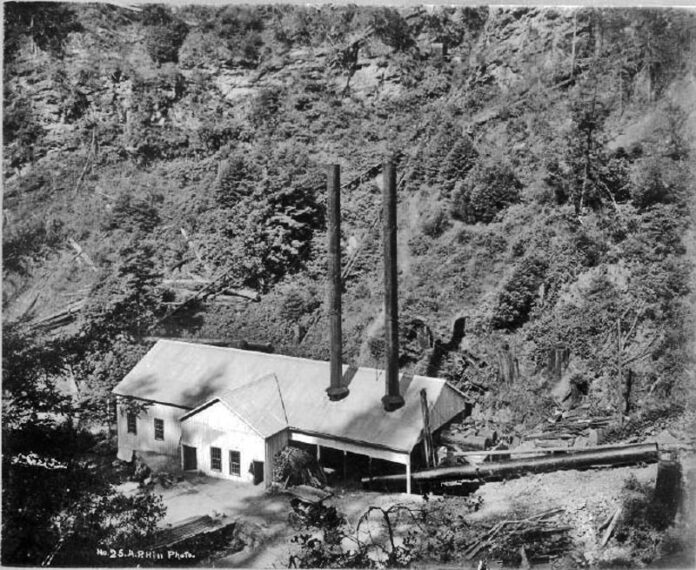

On summer nights, lamps glowed on either end of Ben Lomond, but the streets of the town remained dark. The plans to use the river current to power the hotel electric systems fell short of expectations due to the severe drought of 1898 and 1899. To keep their lights on, both hotels had to rely on the steam power of Silvey’s shingle mill.

Although both hotels insisted that the summer season of 1899 had filled their suites and cottages, the lessees of each quietly left town before it ended. “A Legacy of Unliquidated Debt Left Behind,” headlined the Surf. “Creditors Will Whistle for Their Pay.” Thomas Bell moved on to a new project — “CampArcadia” (the future Mount Hermon) — selling his interest in the Rowardennan to other local capitalists.

In the spring of 1900, the residents of Ben Lomond were cheered by the promise of a new source of electricity to light their streets and homes. The Big Creek Power Company, which provided power to Santa Cruz, constructed a high-power line along the ridge of Ben Lomond Mountain to the winery owned by one of its directors. From there the wires were extended down Alba Road to the outskirts of town.

As the work neared completion, the citizens of Ben Lomond realized that there was a catch. Because the Big Creek dam generated high-voltage power, a transformer had to be built to enable residential use. When the company demanded a guarantee to cover its $1,000 additional cost, the citizens of Ben Lomond called a hasty meeting at the public hall on Mill Street.

Although many residents were willing to subscribe to the new service, it became clear that their pledges fell short of the required deposit. Without the cooperation of the hotels, the opportunity would be lost. Somewhat reluctantly, D. W. Johnston took the lead, offering to cancel his contract to receive power from the mill, and rely on the new line, “although the expense would be more.” When the proprietors of the Rowardennan matched his offer, the Big Creek representative expressed satisfaction and the audience burst into applause.

The power was switched on before the end of June, 1900. “With over thirty street lights along our main thoroughfare in addition to the many private lights,” agreed the Mountain Echo’s correspondent, “the illumination gives the place quite a handsome appearance during the evening.”

Randall C. Brown is a local historian and is a member of the San Lorenzo Valley Board of Directors.