As a third-generation helper of the homeless, there are a lot of stories to tell. My paternal grandfather was homeless during the Great Depression. He walked on foot from Arizona to New York City where he was arrested for vagrancy. Once married and settled down, he regularly brought home vagrants for dinner and let them spend a night or two in the basement. One time he read on the front page of the morning paper that the fellow he’d fed, housed, and shared breakfast with that very day had robbed a bank the day before and was on the run.

Growing up, my dad did the same regarding strangers in our home. Some highlights include a former mafia ‘hitman’ who’d been shot six different times by the police. Each time the bullet had passed clean through and once in a while he’d display the matching pattern of scars on his front and back. One young fellow my dad brought home didn’t know how to read or write. My mom was a teacher at Boulder Creek elementary at that time and, after living with us for ten years, he was making good money as a manager in Silicon Valley.

At the age of five, my family was living on a former sheep ranch in Humboldt County where about 30 beds were available to young runaways and those trying to kick addictions. It was an early and powerfully formative experience wherein I observed firsthand the effects of life trauma, addictions, and homelessness without being among the casualties myself. By the time I faced the temptations of drug and alcohol abuse as a teen, I’d seen the results so many times already that there was really not much appeal. I’d witnessed thoroughly that a crisis like homelessness is not a choice; it’s the end result of lot of previous choices.

Family traditions don’t die easily and over the years I learned a lot of lessons about humanity by bringing home all sorts of homeless folks. I always assume the best about a person no matter what their lot in life. But when I spent a bloody hour talking a man out of committing suicide while he attempted to slowly pushed a large knife through his liver, I finally accepted the terrible truth that some people will not, or cannot, change; the wounds are too deep and the cure too foreign.

Homelessness is nothing new to mankind. In 1200 B.C., Odysseus wandered for ten years before he found his home. Around 740 B.C., God told the people of Israel, “Share your bread with the hungry and bring the homeless into your house” (Isaiah 58:7). In America, homelessness was first recorded in 1640 after the English drove rebellious New Englanders from their homes for the first time. Executed in 1930, America’s first serial killer, Carl Panzram, spent years as “a hobo riding the rails”. Growing up in the early 1950s in east San Jose, my father spent many a summer afternoon hanging out with the hobos camped near the railroad tracks, hearing detailed stories of wars and wanderings. Most of them were good men, just down on their luck and looking for a break.

As a California native, I’ve seen a lot of homelessness. From the Mexican border to Lake County, CA, I’ve helped build homes for families, feed the elderly, and counsel homeless youth. Between the good weather and the free benefits, California hosts 53% of all the homeless in America (projecthome.org). That’s around 300,000 men, women, and children in our state alone. And according to the National Coalition for the Homeless, 25% are severely mentally ill (and as much as 33%; Wikipedia), and 64% or more are addicted to drugs and / or alcohol.

We have to help the homeless. We simply must. But the mental illness and addiction factors of our current crisis make it very hard, as neither facilitates good decision-making nor consistent health-increasing behavior.

In the past, I had good luck helping the homeless. A crack addict we took in long ago has been fairly stable and employed for years now. We helped employ one fellow who was just out of prison and he saved up enough money to return to his extended family in the Midwest. Two years later, he traveled back to Felton just to thank us. In two years, he’d worked hard, bought a house, and was a foreman at a quarry. It brought incredible joy to us to see just one person succeed out of the many we’d helped over the years.

But to be perfectly honest, it seems like helping the homeless is getting much harder. In the last few years I brought a man home, housed and fed him, asking nothing in return. In a very short time, he started harassing me for not giving him the “quality of life” that my wife and kids had. When I shared with him the philosophy of work-ethic, self-control, and delayed gratification that led us to our current quality of life, he mumbled something along the lines of “Yeah, that’s what everyone tells me” and left without even a thank you.

Another time, our high school youth group was passing out food and blankets during the winter and a woman screamed at the kids, “I don’t want your food and blankets! I want your yard!” And a homeless man, living in his van, allowed to park in our church parking lot for three months free of charge, defecated on the floor of the church kitchen when we asked him to leave. We’d even gotten him a better running van, but he rejected it saying, “I don’t want to live in a regular van anymore. I want a camper van.”

Most recently, when leaving church after an evening service, a homeless man stopped me in the parking lot. I rolled down my window, he asked for $25 for a bus ticket, and I apologized for not having any cash on me. Wanting to reassure him of my sincerity, I held up my wallet and opened it saying, “Really, look, I have no cash.” To my surprise there was a $5 bill in the open wallet and, rejoicing, I took it out and gave it to him. “That’s wonderful,” I shared, “I really didn’t think I had any cash and there it was!” He looked at the $5 bill in his hand and then raised his eyes to mine. There was a distinct look of contempt on his face, and he replied, disgusted, “Great. Now I’m $20 short.”

For me at least, it’s very difficult to help the homeless when faced with these kinds of attitudes. And when we ‘help’ a person who is thankless, uncooperative, addicted, lying, and consistently making poor choices, we’re actually not helping; we’re enabling their dysfunction.

According to the Weingart Center in Los Angeles, for $10,000 a homeless person can be put through an in-depth program that helps them get housing, food, a job (and the training to keep it), as well as case management and follow-up support. By contrast, it costs an average of $35,000 a year to leave someone on the street: ER / hospital visits, mental health care, food stamps, and police funding. If the person goes to jail, the cost increases to an average of $47,000.

So, if we already spend more than it costs to fund the necessary programs, why are the homeless, in general, not responding to the opportunity? In my personal experience, the answer is in the statistics. Conservatively, 75% of all homeless have a debilitating degree of mental illness and / or chemical addiction. Potentially, that stat is running as high as 97%. If these statistics are true, we don’t need tax-funded needle exchanges, legal homeless camps, or more money to give to the homeless directly. We need to take that $35,000 – $47,000 per person we are already spending and open residential / permanent housing programs for both the mentally ill and the addicted.

And even if we do this, our expectations should be reasonably low. The National Institute on Drug Abuse states openly “treatment for drug addiction usually isn’t a cure, but addiction can be managed successfully,” and there is a 40-60% relapse rate depending on the specific addiction. Similarly, as of today, mental illness can be treated but not cured. And with both addiction and mental health programs, the National Institute of Mental Health reports a 75% dropout rate from treatment. Psychology Today’s contributor Dr. Stephen Seager (‘BrainTalk’) refers to this dropout rate as a ‘phenomenon’ because it cannot be rationally explained. When offered all the appointments, programs, financial aid, support networks, counseling, and medications required, 75% of all participants voluntarily cease treatment.

We have to help the homeless. We simply must. But we also have to face the hard fact that all the tragedies of life cannot be avoided or cured. And that most of us do not really choose to break bad habits and make major life changes until we have been allowed to hit rock bottom. Give the homeless your time, energy, and friendship. Buy them what they need, but, in my opinion, it’s best not to give cash due to the addiction rate. As a community, let’s be kind to the homeless for they already bear the heavy weight of their own life choices. But our strategy to help them cannot be founded on empathy alone. It has to face the facts as well.

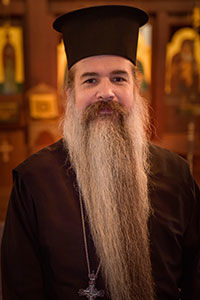

Father Thaddaeus Hardenbrook (MA, MTh) has lived in the San Lorenzo Valley since 1973, attended SLV high school, Cabrillo College, UCSC, and San Jose State before turning his studies from literature to pastoral theology. Having grown up in Boulder Creek, he now resides in Ben Lomond with his wife and four children, and is the senior priest at St. Lawrence Orthodox Christian Church in Felton.