Fred Swanton embraced the role of promoter but left the technical side of the electrical business to his long-time associate, Ed Lilly. The entrepreneur was determined to realize his goal of damming the San Lorenzo for power. But, for once, the engineer believed that Swanton’s plan was not ambitious enough.

California electricians had closely followed the progress of Nikola Tesla’s work at Niagara Falls. That summer, after several years of construction, the giant dynamo at the powerhouse had been run at full speed for the first time. An invited audience of 150 engineers and scientist were, as noted by the Sentinel, “filled with enthusiasm.” The inventor confidently predicted the problem of transmission of power long distances over high-voltage lines was solved — that Niagara power would soon be sold in Chicago and New York City.

“The air of California,” concluded the editor, “has all at once become filled with talk about setting up water-wheels in lonely mountain places.”

As opponents of Swanton’s plans pointedly observed, the San Lorenzo River was notoriously fickle. Even the optimistic promoter admitted that the one thousand horsepower generated during the winter would be reduced by more than half during the dry season, while critics expected a more extreme drop in potential.

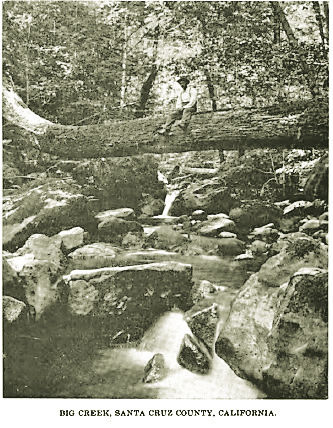

There was, however, one well-known local waterfall. On an August camping trip up the coast, a Sentinel correspondent spent time at Big Creek, nearly 20 miles from town.

“This creek was well named,” he noted, “and it has so much fall. What attracted my attention most was the amount of water power going to waste and doing the world no good. Why not use this power to generate electricity?”

A tributary of Scotts Creek, Big Creek had been a popular destination for Santa Cruz vacationers for many years. It was a famous fishing spot, frequented by steelhead and silver salmon. In fact, Fred Swanton had fond memories of a visit when he and a friend landed 700 “speckled beauties” in a day and a half. Without much fanfare, Swanton changed his mind. At the beginning of November, he spoke confidently of plans to begin work on a water power plant within 30 days but offered no specifics. The following week, Ed Lilly quit his job with the Electric Light and Power Company and entered the employ of the new water power company.

As it happened, most of the real estate around Big Creek was in the hands of friendly speculators, including Judge J. H. Logan, a sponsor of the Santa Cruz Electric Railway. When the work of purchasing water rights, rights-of-way, and dam sites from local investors was wrapped up, Swanton headed to San Francisco to present his plan to the area’s largest landowner, Timothy Hopkins. The adopted son of a founder of the Southern Pacific Railroad, Hopkins controlled thousands of forested acres in Santa Cruz County, including most of the Big Basin. Swanton was delighted with the outcome of the meeting.

“He accepted my own figures as to the price of his water rights. The interest he showed was indeed gratifying.”

On December 4, 1895, Swanton unveiled the new plan.

“Our object in harnessing Big Creek,” he told the press, “is that the power is greater than the San Lorenzo River. The fall is ten times greater, and besides, Santa Cruzans who own water rights will directly reap a benefit.”

(To be continued.)