The mysterious malady was arbitrarily linked with Spain, where thousands, including King Alfonso, were infected in the spring. As might be expected in 1918, some Americans were certain that “this new evil, like other evils of the war, must be traced to German origins.”

The virus crossed the Atlantic on freighters and ocean liners. New York City health officials were unconcerned. The port’s head doctor speculated that the “Spanish influenza” was “nothing more than the grippe.” By the end of September, over 6,000 cases were reported there in addition to the 30,000 in the Boston area. “If the people of this country do not take care,” one alarmed observer commented, “the epidemic will become so widespread throughout the United States that soon we shall hear the disease called ‘American’ influenza.”

The government in Washington was not immune. In September, with the Senate majority leader and the Speaker of the House exhibiting symptoms of the disease, Congress united to pass a bill appropriating $1 million to fight the growing epidemic. Among the victims was Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose life hung in the balance for a time.

Dr. Blue, the surgeon general, warned Americans what to expect, noting that an estimated 20 percent of the population of Europe had been afflicted. “The symptoms of Spanish influenza,” he advised, “may be distinguished from those of an ordinary cold by prostration and aches and pains in the head and back. There is no prolonged period of waiting to know whether your cold is influenza. If you have it, you’ll probably know it the first day.”

The epidemic reached San Francisco in the final week of September. The city’s health officer, Dr. Hassler feared the worst, noting that the disease “spreads quicker than any disease known and attacks all classes.” Simultaneously, Los Angeles reported half a dozen cases. By the end of the first week in October, the numbers escalated into the hundreds.

On the 5th of the month, Surgeon General Blue issued new, stronger guidelines, advising that: “the only way to stop the spread of Spanish influenza is to close churches, schools, theaters and public institutions in every community where the epidemic has developed.” The hard-hit city of Seattle immediately adopted the recommendations. In San Francisco, where 400 cases and 5 deaths were reported, officials advised citizens “to keep off crowded streetcars.” Los Angeles responded by closing “indoor amusement places” as the film industry agreed to suspend operations.

. Meanwhile, in Santa Cruz, newspapers noted that there had been “none of the malady” in the city. On the 12th, however, locals were shocked out by news of 2 deaths of young people from well-respected families. Carlton Canfield had graduated from Santa Cruz High in June, and gone to college in Los Angeles, where he succumbed to pneumonia brought on by influenza. Grace Baldwin, twenty-something daughter of a local bank president, who passed away in Massachusetts, had been a popular teacher at the Mission Hill school and an active participant in social life.

As the grieving parents brought the remains of their loved ones home, the authorities instituted the first precautionary measures, including temporary closing of movie theaters. Santa Cruz Health Officer A. N. Nittler took on the role of spokesman. His tone was reassuring—noting that there was no epidemic here and, if it appeared, he believed that it could be controlled. The doctor did admit, however, that two cases had been reported in East Santa Cruz, noting that one patient, Loula Jones, had just returned from a visit to New York.

On the 15th, the public learned that Miss Jones had lost her battle with the virus. That afternoon, Dr. Nittler announced expanded measures to prevent the spread of the disease. The list of mandated closures now included the schools, churches, and meeting halls. People on the streets and in the stores were advised to avoid forming groups.

San Francisco instituted similar measures a few days later. On the 21st, as the local patient count increased to 61, Dr. Nittler tightened the rules in Santa Cruz, ordering the closure of the public library and all its branches, shutting down poolrooms, and forbidding indoor funeral services. Many businesses not covered by the orders adapted their routines. Employees of one of the city’s grocery stores were among the first to don preventative masks.

As the number of reported cases reached the hundred mark, the health officer urged the general public to get into the habit of wearing masks when congregating with others. Nittler’s growing concern was personal as well as professional—his sister, a nurse in an Oakland hospital, had been infected.

Alarming statistics continued to pour in from other California cities. The Evening News urged “that steps should be taken to curtail travel into Santa Cruz from cities and towns where the influenza exists in virulent form. Unnecessary trips by Santa Cruzans to San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose and return should certainly be abandoned.”

The city council held a special session on the 26th. Almost all the local doctors were present. Dr. F. E. Morgan, a veteran practitioner, “asked with a smile whether or not the physicians themselves would be forced to wear a mask.” The result was an ordinance, effective immediately, compelling “every person within the city of Santa Cruz” to don masks when on the street or in public.

The press was pleased to note that the public accepted the tougher rules “without kick.” “Of course, the masking has its funny aspects,” commented the News. “Dr. F. E. Morgan not only wears his mask with grace, but he smokes his cigarette right through it. He claims that it’s a germicidal cigarette.”

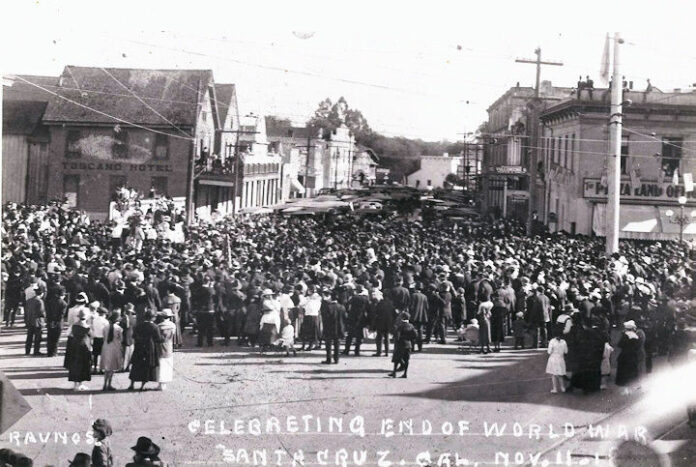

Although roughly 200 Santa Cruzans had contracted the bug by the end of October, only two had developed pneumonia. The newspapers were optimistic. “The masks have turned the trick,” the News commented on the 30th. “Influenza cases in Santa Cruz have fallen away off in the last twenty-four hours.” “Hundreds now come downtown and attend to business or pleasure, where only a few appeared on the streets at all last week.” (To Be Continued)

Randall Brown lives in Boulder Creek and works in Felton. He wrote the history of the SLV Water District, co-authored “Santa Cruz’s Seabright.”