A Caltrans worker explained last week why the rocks, mud and trees from the latest landslides that closed Highway 9 south of Felton were not being removed: “The mountain is still moving.”

The hillside along a half-mile section of the state two-lane road that follows the San Lorenzo River has been unstable since early January, frustrating cleanup efforts. Caltrans announced March 10 they hoped to open Highway 9 by March 31.

The hundreds of landslides that occurred in the Santa Cruz Mountains since early December have blocked roads, destroyed homes and public lands, and raised new fears about the safety of living in mountainous terrain.

Geologists who are experts in landslides understand how they occur. But they can’t say where or when they will occur.

For this reason, they remain one hazard for which property owners cannot obtain insurance.

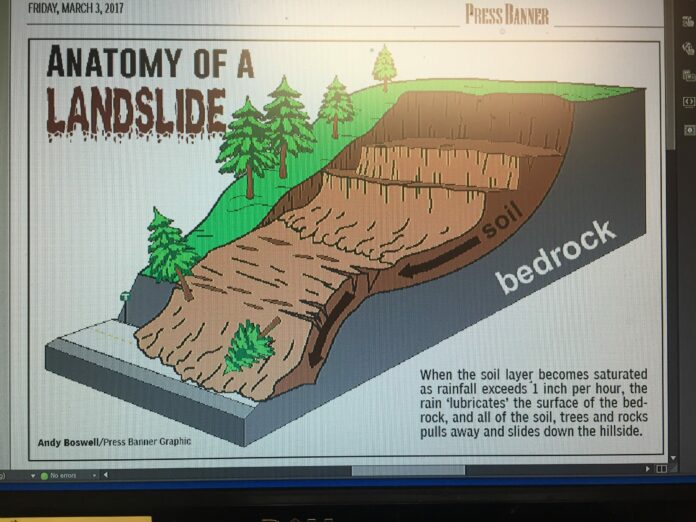

“When you have a steep hill slope and it starts to rain at the rate of more than 1 inch per hour, you get water percolating through the hillside soil,” explained Noah Finnegan, associate professor of geomorphology – the science of erosion – at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“At some point, this changes the the frictional properties of the land, and the rain water acts a kind of lubrication,” he said.

“And the landscape comes alive.”

CalTrans engineers say no real remediation can occur until at least a month after the rainy season ends. Any efforts before then, such as occurred along Highway 17, are temporary at best, they say.

Finnegan explained that there are two different categories of landslides.

One kind, the most common, is the “creeping” variety, where the one-to-two meters of soil on the bedrock hills become saturated and simply slid down the hill, taking trees and sedimentary rock with them.

“The ground serves as a conduit for the water flow, and high water pressure builds up inside he soil,” Finnegan said.

The second type of landslide, less common but even more dangerous, is when the bedrock itself becomes weakened and compromised by growing water pressure between weak layers of rock. The bedrock fails and layers of clay and sandstone, of sedimentary rock, virtually explode in single, fast-moving catasprophic landslide.

This is what happened at Love Creek in Ben Lomond in 1982, he said.

Both types are impossible to predict, he said.

Finnegan said that the two big slides that have occurred on Highway 17 this winter appear to represent failures within the bedrock, not just sliding soil. There is evidence that the rock is pretty fractured and broken up, he said.

With regard to the comments by the Caltrans worker about conditions along Highway 9, Finnegan said “it is pretty common for a landlslide to keep moving,” he said. “It can flow like molasses and it is hard to predict when these will stop.”

Finnegan said one of the key questions facing landslide scientists is trying to understand they occur where and when they occur.

His advice to homeowners?

“If you are building on a hillside, you probably shouldn’t be building there.”

“But, to try and avoid problems, you can anchor on bedrock,” he added.

Along highways, a typical remediation is to build large walls with drainage, to keep hillsides from sliding, say Caltrans geologists.

He said he and his colleagues are working to with high-resolution laser photography to begin making landslide hazard maps, high-resolution topographic maps, based on probabilities, that can “see” where landslides are. This year may give them one of their best living laboratories for their work, he said.

Landslides in soil…typically occur during high intensity rainfall events…

He also said that the water pressure buildup may not end when the rainy season ends. Some landslide failures have occurred one to two months after the rain stops.