On July 4, 1776, America’s first Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, officially breaking the young country’s ties with Great Britain.

Independence Day, the anniversary of that action, is associated with fireworks, parades, barbecues and patriotism. But to maintain those festivities and the freedom the country enjoys, the United States has fought in many wars.

The Press-Banner took a moment this week to interview two World War II veterans. Both live inScottsValleyand play poker and bingo at the Scotts Valley Senior Center.

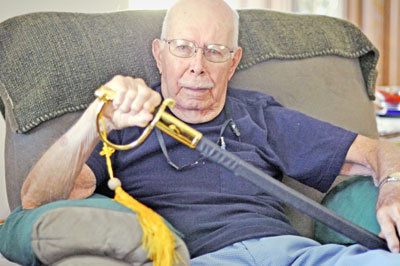

Dave Faunce

On Dec. 8, 1941, 17-year-old high school senior Dave Faunce, spurred by anger at the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor the day before, went down to a Philadelphia courthouse to enlist in the Navy to become a marine.

But it was not to be.

His mother stopped him and insisted that he graduate from high school before enlisting. So just after his 18th birthday, he signed up.

“Everybody was patriotic, and that (the Japanese bombingPearl Harbor) was a good reason to go to war,” Faunce said.

He enlisted April 9, 1942, and completed boot camp in Parris Island, S.C. He was assigned as a heavy artillery crewman on the 155 mm howitzers as part of the just-formed 9th Marine Defense Battalion of the 3rd Marine Division.

After several stops, the battalion was shipped to the Solomon Islands east of Papua New Guinea, where Faunce participated in the defense of Guadalcanal Island from March 30 to June 30, 1943, after the island had been taken in a battle stretching between August 1942 and February 1943 as part of the first offensive by the allies against Japan during World War II.

During the occupation of Rendova Island in the Solomon Islands, the battalion earned a presidential citation for destroying 24 Japanese bombers with 90 mm anti-aircraft guns.

“We got bombed the first day and then set up with anti-aircraft guns the second day, and that’s when we got to work,” Faunce said.

They were in action again at Kolombangara Island from Aug. 31 to Oct. 3, 1943, before being relieved and shipped toGuamas an occupational force.

After 28 months in the South Pacific, Faunce’s battalion was sent home. He was shipped to the Naval Hospital in Oaknoll for testing and then to a malaria recovery facility in Klamath Falls, Ore., to convalesce from a severe bout of the illness.

He was discharged April 8, 1946.

Faunce went on to work in fire protection and security with Ford Motor Co. inMilpitasand retired when the plant closed in 1983.

He married and had two sons, who have both died, and one daughter, who lives in Scotts Valley. He moved to Oklahoma following his retirement, where he joined the Veterans of Foreign Wars post in his town and was named chaplain, because he regularly attended church.

Now 88, Faunce moved from Oklahomato Scotts Valley a little more than two years ago. He recently participated in the Felton Remembers Parade to represent World War II.

“There are a lot of bad memories. However, it was a job that had to be done,” Faunce said. “Like (President Harry S.) Truman said, ‘The buck stops here.’”

Willard Roberts

With his father unemployed, Willard Roberts had to go to work in 1939 to support the family as soon as he graduated from high school inWisconsin. But in 1942, with World War II raging, work for his father was abundant, and Roberts wanted to join the war effort.

He enlisted in the Navy and was sent to Naval Training Station Great Lakes inIllinoisfor an abbreviated eight-week boot camp before attending gunfire control school, where he earned the rank of petty officer third class. He was quickly assigned to the Edward H. Allen E-531 Destroyer Escort — a ship that had not yet been built.

“The whole ship was built in one month,” Roberts said. “Workers in those days were eager to make money because of the Depression.”

The naval recruits were as green as the ship, he said.

“Many of the people on my ship had never been to sea, even the officers.”

The E-531’s job was to protect convoys and carriers during the Battle of the Atlantic. Its primary mission was as an antisubmarine force, as it protected supplies, troops and materials that were rushed from the U.S. to Great Britainto support the front lines.

“The (German) U-boats would pick on transports,” Roberts said.

The E-531 patrolled the East Coast all the way down to the tip of Florida, searching out U-boats. Although never fired upon, Roberts, a helmsman tasked with steering the ship, recalls having to guide the ship directly into 30-foot swells in icy Atlantic waters during a storm.

“Green water was coming over the whole ship,” Roberts said. “The ship was getting iced up, and the officers were scared it would capsize.”

After some time, the E-531 became a “school ship” that trained new recruits by practicing firing at night, dealing with smoke, refueling at sea and other important skills.

“By 1945, the Battle Atlantic was won,” Roberts said. “The U.S. built cheap carriers that carried 20 planes. This was very effective against submarines, because you can search for long distances.”

Roberts was promoted to petty officer first class and discharged in October 1945 and joined the active Naval Reserve. He took part in a victory march on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., the day the war ended inEurope.

He immediately signed up to study electrical engineering at University of Wisconsin and after three years went to work for a steel company and then for General Electric, where he worked 19 years.

With his wife, Vera, now deceased, he had two children, Sally and Errol.

“I didn’t mind the Navy,” said Roberts, now 90. “It was transformational, because I would probably be pounding nails. I had no idea I would ever go to college — no one in my family had ever gone to college.”