When I drive to the top of Bear Creek Road, looking down to Loch Lomond Reservoir and across the bay to the Ventana Wilderness, I imagine what our land would have looked like before the European invasion. What grew here? Ate here? Roamed here? What mark would American Indians have made?

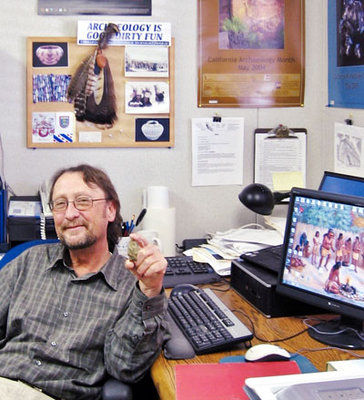

Most Hollywood movies portray Plains Indians, who lived in easily transportable teepees and who followed the game. Our land’s early people also hunted, gathered and had seasonal camps — “but they weren’t nomadic,” said Mark Hylkema, state archaeologist, at his Santa Cruz District office.

“Ohlones, which became a catchall for all 50 tribes from Monterey to San Francisco, never saw themselves collectively as a nation,” Hylkema said. “They saw each tribe as an individual political group. Big Basin was home to several tribes who would use the interior.

“Generally, the interior, the redwood mountains, was not supportive of residential sites, so their villages weren’t there, but their work stations were.”

“They were not nomads,” he emphasized again. “They had small territories, about 10 by 10 miles, so you might look at it like a big house, and Big Basin was another room in the house.”

Hylkema will lead our next watershed walk through important natural and anthropological sites at Big Basin State Park on June 4.

“These were politically complex people; they had leadership, rank, status and money,” he said. “So they were able to move resources across time and space. And they had an economy. So Big Basin is interesting, because it is still being discovered in many ways, archeologically.”

The redwood forest from which the tribes made a living was not constant, though.

“There’s been a lot of environmental change, and as ecological zones shifted back and forth, Indians were on that roller coaster, too, for the last 8,000 years. You have areas that didn’t have redwoods, then do, then don’t, then do again. Native American sites are in areas you wouldn’t expect them to be, and that’s because at one time they weren’t as densely forested.

“The forest retracts and expands, and the sides of those sites get overgrown again, so it’s hard to find an archeological site in redwood mountainous habitat.”

Unlike many sites that have been explored in deserts, the redwoods usually hide their Indian secrets.

“They are there. But you don’t really see them, because you can’t see the forest for the trees.”

Hylkema began to think like an Indian while growing up in San Jose. He became friends with a member of the Lakota tribe whose family had been resettled by the government in the 1950s from the group’s poor and depressed reservation. The friend’s father was a holy man who taught Hylkema how to use the pipe for prayer and to speak Lakota.

“One of the things I look forward to on this walk is showing what resources were in the forest that were useful to the people and to understand that Indians went there specifically for certain plants and animals they needed,” Hylkema said. “They managed the natural landscape by pruning, tilling, burning. So it wasn’t just a hand-to-mouth subsistence. It was actually more of a garden landscape.

“Since they aren’t doing that anymore and haven’t for a couple of hundred years, the landscape has become wild.”

California once had the greatest linguistic diversity in the world; more languages were spoken here than anywhere. The area that became California also had the greatest population density in all of North America.

“Part of that was their ability to manipulate the land and produce,” Hylkema said. “They were right on the edge of agriculture.”

On the June 4 walk, the archaeologist will talk about who the Ohlone were at the time of European contact in the 1770s and what happened to them.

“I’ll talk about which tribes were at Big Basin,” he said. “We’ll try to get an introspection of what life was like for them. We’ll look at artifacts and see a bedrock billing station where they used to make acorn into food. We’ll also visit the monument that is the epicenter of the birth of the California conservation movement, the first conservation movement in the world. Big Basin is the first park purchased by the public for conservation.”

Where are the Ohlone now?

“They are still here,” Hylkema said. “I work with their descendants. They never disappeared. We just became many.”

Carol Carson is a writer and naturalist who has been a docent at Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, taught classes on Big Basin State Park for UCSC Extension, and organizes nature walks through a grant from the San Lorenzo Valley Water District. She can be reached at ca****@*********on.com.

At a glance

– To take part in the June 4 nature walk with archaeologist Mark Hylkema in Big Basin Redwoods State Park, e-mail Carol Carson at ca****@*********on.com.