The Scotts Valley Water District is refusing to refund more than $1,750 in overpayments it collected from a Green Valley Road resident, over the past several years.

While the drinking water provider admits it received $4,381.35 beyond what it should have from Jim Chelossi, since Feb. 2017, it says it’s only willing to return three years’ worth of overpayments—$2,597.84.

“I don’t have a problem with them making the mistake—just pay me back,” Chelossi said. “I think they’re going to find there are other people that this has happened to.”

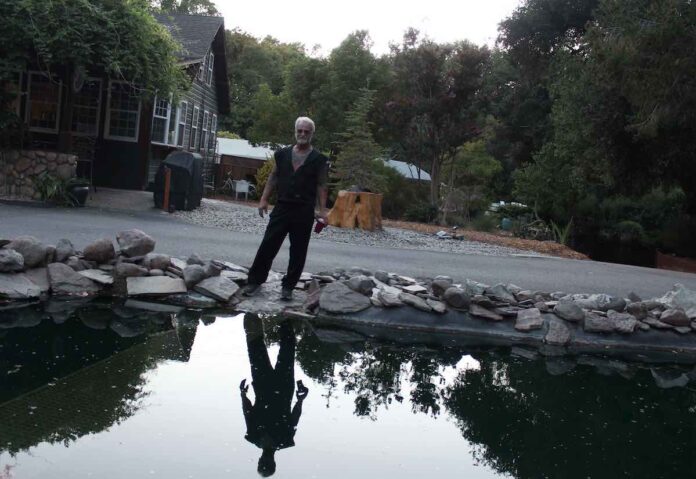

The predicament facing Chelossi, who’s known around town for patenting the now-ubiquitous coffee sleeve, is a result of a system-wide billing switch that happened in 2016.

Under the current system, homeowners are charged different rates based on how much water they use, and multi-family properties get to use a larger volume before higher rates kick in.

But Chelossi was being charged as if he was on a single-family parcel—for around five and a half years—when in reality there are three units on his land.

Some months he’d overpay by $4.63 or $5.19; other times he’d be charged $225.01 or $223.29 above what should’ve been billed.

It all began to add up. But he says he had no idea it was happening.

“When I get a bill, I pay it,” he said. “I don’t look at it much ever.”

A couple of months ago one bill seemed particularly high, so he decided to take a closer look, he says.

“They admitted the mistake,” Chelossi said. “And they only offer me partial. I don’t understand that.”

He believes he’s paid over $14,000 in total since the billing switch—with around $7,500 in overpayments.

Piret Harmon, SVWD’s general manager, says the district’s legal counsel told her they only have to return three years’ worth, due to the statute of limitations.

In fact, she says giving Chelossi his money back would be imprudent.

“We are using ratepayers’ money, so we want to make sure there’s no gift of public funds,” she said, suggesting Chelossi bears some responsibility for taking so long to check his bill carefully. “There needs to be some sort of timeline, and that’s why the State law puts it at three years.”

However, she notes Chelossi is welcome to plead his case before the utility’s board of directors.

“They can choose to overrule me,” she said. “If I start making an exception for one customer it almost opens a Pandora’s Box.”

On Sept. 14, Chelossi lodged an official complaint with the City of Scotts Valley.

In his submission, he referenced the recent case where the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power agreed to give back 100% of customer overpayments—which even involved an FBI search—after PricewaterhouseCoopers overhauled its customer database in 2013.

Chelossi’s been researching case law, and found a blog post from the nonprofit Municipal Research and Services Center, a Washington State organization that assists local governments, that suggests the three-year statute of limitations might only begin once a customer discovers the overpayment.

Chelossi’s property has now been reclassified as multi-family in the SVWD system, and he’s started getting the discounts he’s entitled to.

But the whole process has left him with a sour taste in his mouth.

“I actually said, ‘You know, I’m not trying to be a hardass,’” he said of an offer he made to settle for five years of repayments instead of the full repayment. “How would you feel? Bullied, really.”