In the 19th century, the old pagan holiday of All Hallows’ Eve was often a romantic occasion. “To lovers,” according to one article, “the feast is the most convenient of all on the calendar. The maiden, on Hallow Eve, is enabled by a temporary suspension of her Christian conscience and some diabolical enchantment, to behold the person of her future husband.”

Many of the prophetic spells involved apples. The oldest trick of all, perhaps, was bobbing for apples. If one did not succeed after three attempts, spinsterhood or bachelorhood was thought to be secured without a shadow of a doubt. Girls used to take an apple and pare it without breaking the rind, then swing the rind three times over their head and throw it on the floor. The form assumed by the apple paring would be the initial of the true lover.

The poet Robert Burns offered the following suggestion: “Take a candle and go alone to a looking-glass; eat an apple before it and the face of your conjugal companion, to be, will be seen in the glass.” Similar results could be achieved by walking backwards down cellar stairs with a mirror and candle.

Another test involved jumping over twelve lighted candles. Each one represented a year — if none was extinguished, the altar beckoned, if all went out, eternal spinsterhood loomed. There was also the time-honored custom of baking a ring, a dime, and a thimble into a cake. The slice containing the ring predicted wedded bliss, the dime, a profitable career, and the thimble, single blessedness.

By the turn of the century, less social activities prevailed. As one former boy admitted in 1912: “Apple bobbing and trips down cellar with a lighted candle and a mirror— were all very well for girls and ‘dress up’ parties, but they weren’t the essence of Halloween. That essence was robbery, destruction, and arson.” Traditionally, “errands of mischief and evil,” were ascribed to “hobgoblins, gnomes, witches, and fairies, but “the small American boy does not believe in witches, and as for fear that no mischief will be done, he does it himself.”

“The young hoodlums of this city,” reported the Santa Cruz Sentinel, “some of whom, we are sorry to say, are female — committed all sorts of vandalism. Gates were hung on telegraph poles, the school bells were rung, a buggy was put on the roof of a blacksmith shop on Front Street — and a ‘for sale’ sign placed on the Episcopal Church. In Boulder Creek boys tied the door of a residence to a fence with some wire, and then rang the bell. When the owner arose to open the door he was unable to do so. Then he went into his yard and fell over wire that had been stretched from fence to fence.”

Bounds were increasingly exceeded. The businesses of Pacific Avenue were a prime target. “Store windows were soaped and mottoes — some appropriate and others not so appropriate — were scrawled in schoolboy hand.” In 1905, “the streetcar tracks on the Soquel Avenue hill were greased and the cars were stalled there for over half an hour,” according to the Santa Cruz Sentinel.

Their patience exhausted, local authorities cracked down. In 1909, potential troublemakers were warned that: “Chief of Police Dougherty and his men will be wearing gum shoes tonight — and woe betides the luckless wight who falls into their hands.” At the height of World War I, a police-sponsored advertisement advised that: “There will be no Halloween celebration tonight.”

When the town fathers of Boulder Creek announced extensive precautions in 1925, vandals surprised them on the night before the holiday. “The high school building,” it was indignantly noted, “is reported as being more or less extensively damaged and disturbed.”

Schools, churches, and shrewd parents took preemptive action by sponsoring social activities, often featuring “Chambers of Horrors.” In Ben Lomond an annual masquerade dance, originally arranged by the young women of the Blossoming Club, raised funds to help save Park Hall.

The reign of the pranksters continued into the Depression, with some concessions to modern times. There were less gates to remove, but “the percentage of doorbell rings mounted rapidly,” and “many motorists were inconvenienced to the extent of having to mop over-ripe tomatoes off their windshields.”

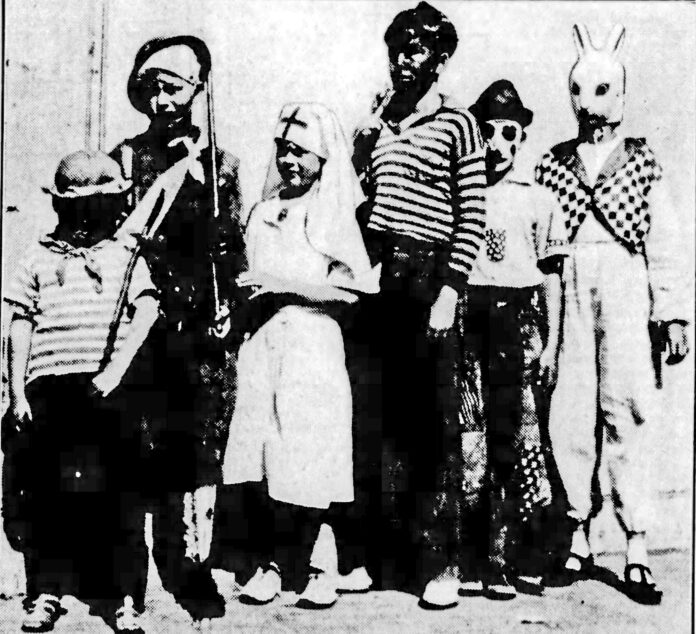

The Santa Cruz Chamber of Commerce evolved a proactive approach. Children who signed a pledge “to refrain from — doing anything that is not good, clean, harmless fun on Halloween,” were rewarded with free movie tickets. The campaign proved effective and, several years later, another attraction was added — a costume parade along Pacific Avenue.

In 1940, the modern era of Halloween in Santa Cruz began. “Something new in youthful racketeering,” observed the local paper, “was reported to police last night as two youthful celebrants, about 10 years of age, hit upon the holiday theme as a chance to cash in. Accosting a housewife, the two youths in Halloween costume, chorused ‘Trick or treat?’ Given cookies and pennies, they went on their way without molesting anything.”

Randall C. Brown is a local historian and is a member of the SLVWD