One intersection with traffic lights. No high school. No movie theater. No transit center. One big shopping center. That was Scotts Valley when I arrived as a reporter for what is now the Press Banner 50 years ago.

But Scotts Valley was not a one-horse town, neither literally nor figuratively.

“Kids rode horses up and down Scotts Valley Drive,” recalled Donna Lind in a phone interview last month. She has been part of the city continuously since 1968, as a secretary, police officer and now City Council member.

In my six years here, I covered a growing city with spirited political battles between liberals and conservatives, mostly over growth, and saw the beginning of technology companies coming to the city.

The politics got nasty: A city councilwoman was recalled, and two planning directors were fired. The city’s first planning director (Jun Lee), former City Administrator Friend Stone and former Police Chief Gerald Pittenger were all later elected to the city council.

Through it all, this was still an attractive place to live. Churches thrived, but you didn’t have to be religious to get along in Scotts Valley. And some people deliberately ignored local politics, especially merchants who didn’t want to alienate customers.

Scotts Valley was my main beat when I joined the Valley Press, based in Felton, at age 24 in April 1973. In 1974, publisher Craig Robinson started a separate paper in Scotts Valley, the Banner. I was named managing editor, a fancy title for sole reporting staff in Scotts Valley, and stayed until leaving for the Register-Pajaronian in Watsonville in 1979. In 2006, the Banner and Valley Press became one paper again, with the current Press Banner name.

Some public officials didn’t like a reporter like me snooping around. I didn’t necessarily like them either, but we all knew we had to get along.

The Scotts Valley Water District once scheduled a discussion on paying themselves a stipend for attending meetings—they were getting zero. During a break in the meeting, the chairman told me the board wouldn’t discuss the issue that night. So I went home.

The next day, district Manager Jack Hinds told me that directors tried to bring it up after I left.

Bob Haight, the board’s attorney, had heard the chairman talking to me. “You told the reporter you wouldn’t discuss it. You can’t bring it up now,” he told the board.

While serial killers were active in other parts of the county in the early ’70s, crime was not a big problem in Scotts Valley.

Chief Pittenger “incorporated community policing before there was a word for it,” Lind said. “He expected officers to get out of their cars and know the businesses, their owners and staff. He did not allow officers to accept a free coffee or discounted meals when that was common throughout law enforcement.”

Once, I needed police assistance. I was talking to six or seven strikers who were picketing the Kaiser Permanente quarry off Mount Hermon Road when one of them pushed me. I was afraid the situation would get worse for me.

I contacted police, and officer Steve Walpole Sr. responded. He didn’t cite anybody—he just told the pickets how stupid they were for tangling with the media. The pickets were more afraid of Walpole’s “assistant,” police dog Duke. Walpole went back to the station, Duke went back to eating dog food, and I went back to interviewing the pickets.

Walpole later became police chief; his son Steve Jr. is now chief.

Students at Bethany Bible College, where the 1440 retreat is now, were rarely a problem for police. But sometimes, Lind said, students sneaked onto the Canham Road property where movie director Alfred Hitchcock kept a second home until about 1970.

“It was on a dare,” she said. They’d bring back a rock or other small item to prove they were there. Eventually, police told students to knock it off.

My favorite lunch place was a 600-square-foot sandwich shop that 28-year-old Erik Johnson opened in September 1973 in Kings Village. The next year, Johnson had a chance to add 1,260 square feet when the space next door became vacant. Another merchant and I were skeptical.

“Too much, too soon,” we agreed. How wrong we were—Erik’s DeliCafe now has 27 locations.

There weren’t a lot of athletic fields in Scotts Valley at the time—Little League was at Vine Hill School, Colt League baseball at the middle school. And the middle school gym floor wasn’t wood, but like something left over from a kitchen remodeling.

But Scotts Valley produced some good athletes, mostly notably Julie Simpson Inkster, the Hall of Fame golfer. She grew up in Pasatiempo, outside the city but part of the Scotts Valley school district. Jim Hart, now Santa Cruz County sheriff, went to Scotts Valley schools, Harbor High and played basketball at the University of Nevada in Reno.

Kerri Walsh Jennings, an Olympic volleyball gold medalist, spent her early years in Scotts Valley and went to high school in San Jose.

Until Scotts Valley High School opened in 1999, local students went to either Harbor or Soquel. That wasn’t necessarily a bad thing.

“Scotts Valley is a neat place to grow up, but it’s good for the students to experience a larger area like Santa Cruz,” longtime Scotts Valley school trustee Marj Bourret told me in the mid-’70s.

School politics were usually tame, except for a 1974 debate over introduction of a sex education class at the middle school. Conservatives led the opposition, and one parent complained that their child would be learning about sex.

“That’s the reason for the class,” blurted out school bus driver Alan Kimball from the back of the room. The school board approved the class.

Scotts Valley now has a theater, a high school, a transit center, multiple traffic signals, and enough stores that you can do most of your shopping here without going to Santa Cruz.

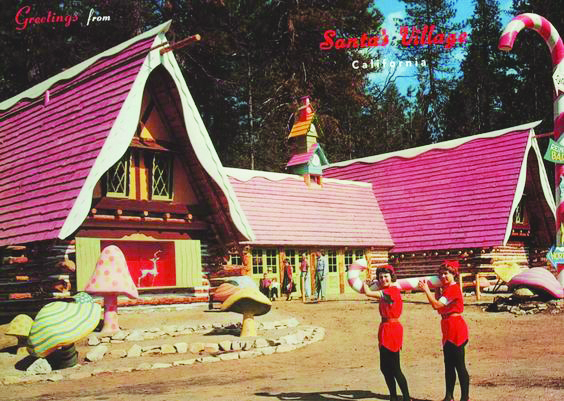

“There are things I miss. I look back and tell people about Santa’s Village,” said Lind, “and I was heartbroken when the golf course (Valley Gardens) closed.”

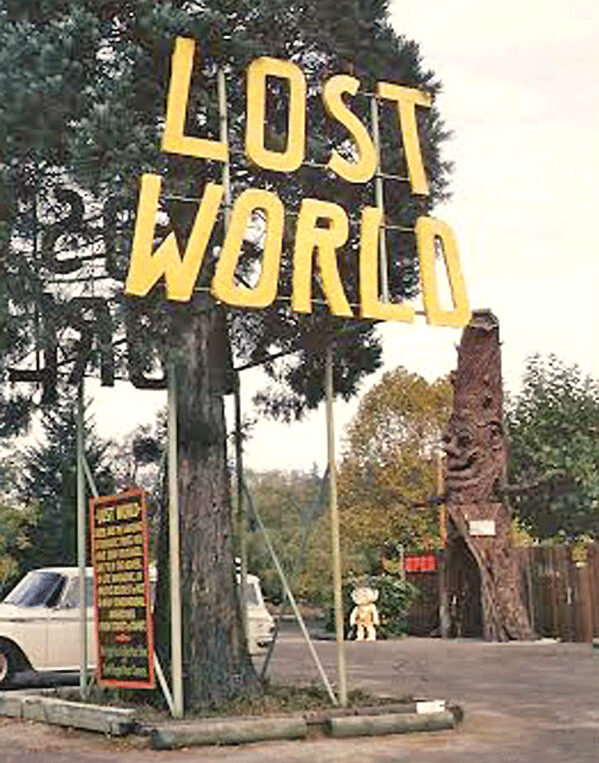

Other landmarks are also long gone: Lost World (fiberglass dinosaurs) and the Tree Circus (trees grafted into unusual shapes), already fading as tourist attractions 50 years ago, and Sky Park airport, which closed in 1983.

Even with clashes over politics and education, Scotts Valley was a friendly place in the ’70s. It still is, Lind said.

“People, when they move here, feel that sense of community. They talk about it,” she said. “They also appreciate that Scotts Valley continues to be one of the safest communities in the state and Scotts Valley Police Department’s long history of community policing.”

Scotts Valley will keep growing. There’s a state mandate that calls for 1,220 housing units in the city in the next eight years.

“I don’t know where you’re going to put them,” Lind said.

After leaving Scotts Valley, Lane Wallace spent 17 years each at the Register-Pajaronian in Watsonville and the Monterey Herald. He lives in Soquel. He can be reached at [email protected].